Category: theology

Why We Need the Creed

In 1993 Contemporary Christian music artist Rich Mullins released his magnum opus, A Liturgy, A Legacy, and a Ragamuffin Band. The flagship song from that album was “Creed,” a hammered dulcimer-driven recitation of the Apostles’ Creed, punctuated by Mullins’ own affirmation: I did not make it / no, it is making me / it is the very truth of God and not the invention of any man.

As a hardcore evangelical (which I still am) and an amateur student of theology (still that, too) I was, at the time, wary of words like “liturgy” and “creed.” My, uh, credo was,

My faith has found a resting place / Not in device or creed / I trust the ever living One / His wounds for me shall plead…

Turns out the late Ragamuffin was onto something a decade or so before the rest of a restless band of evangelicals, exhausted from the culture wars and endless schism, caught up with the value of a liturgy and a common creedal legacy.

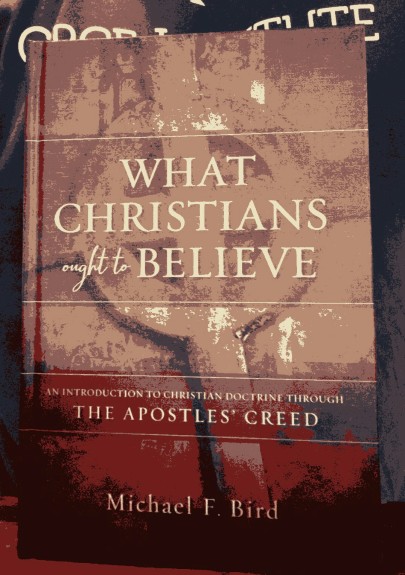

Enter a man for the moment. Michael Bird is lecturer in theology at Ridley College, an evangelical Anglican theological school near Melbourne, Australia. Bird’s own life has followed a trajectory that resonates with many a Western evangelical: an unbeliever as a youth, a machine-gun toting paratrooper in the Australian military (the Aussie version of Bear Grylls), converted in a Baptist church, then discovering the Anglican tradition. With a Ph.D. in New Testament studies Bird is a prolific author of scholarly articles and books, and maintains the popular blog Euangelion (link in the right column). Writing from a “post-post-modern” perspective, Bird is keen to speak to an audience of believers and skeptics alike trying to figure out which end is up.

Enter a man for the moment. Michael Bird is lecturer in theology at Ridley College, an evangelical Anglican theological school near Melbourne, Australia. Bird’s own life has followed a trajectory that resonates with many a Western evangelical: an unbeliever as a youth, a machine-gun toting paratrooper in the Australian military (the Aussie version of Bear Grylls), converted in a Baptist church, then discovering the Anglican tradition. With a Ph.D. in New Testament studies Bird is a prolific author of scholarly articles and books, and maintains the popular blog Euangelion (link in the right column). Writing from a “post-post-modern” perspective, Bird is keen to speak to an audience of believers and skeptics alike trying to figure out which end is up.

His latest book, What Christians Ought to Believe, serves to help the scattered ragamuffins get on the same page as their world becomes increasingly post-Christian:

Know this: the world of our parents and grandparents is no more. We have to realize that the Western world has changed; it either already is or else is very quickly becoming decidedly post-Christian and radically secular. The church is no longer the chaplain for Christendom; it is now a recalcitrant resistance to a secularizing agenda. The church is no longer the moral majority; it is now the immoral minority with offensive views on everything from family to religious pluralism and sexuality. The church is no longer the first estate but more like an enemy of the state through its unflinching devotion to God and its uncompromising refusal to bow the knee to cultural and political lords of the land. [p. 203]

Written like an Ignatius of Antioch — or a soldier who’s slept in some trenches and eaten a few bugs.

His book explains why the Apostles’ Creed is indispensable to shoring up the faith of the faithful, and shoring the faithful together.

As Bird shows in his helpful appendix, the creed was developed from a series of catechetical questions attributed to Hippolytus of Rome around 215 A.D. Each line reads almost identically to the “Do you believe…?” questions from the catechism. As a Western document the Apostles’ Creed never caught on in the Christian East, though it predates the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed by more than a century. But as a compact statement it marks the key signposts of the faith identified by the early church.

Bird expounds on the significance of each line of the creed. For example, only three humans are mentioned: Jesus, Mary, and Pontius Pilate. Why the latter? Because Pilate’s inclusion places the central event of the Christian story within recorded human history, as if the creed dares the reader to look into the writings of Philo and Flavius Josephus to ponder whether the events of Christ’s life were historical or fictional.

Bird gives four reasons why the Apostles’ Creed invigorates believers’ faith:

1) In a liturgical context, its recitation marks a logical transition from the ministry of the Word to the Lord’s Supper. “We recite the creed after sermons to remember that we weigh all teachings against the fabric of Scripture as it has been taught in the churches.”

2) The creed promotes unity and fellowship among believers, “a faith that transcends denominational divisions.”

3) The creed places us within the story of God’s plan to usher in the new creation. We are situated with other believers of the past, present, and future.

4) The creed helps strengthen one’s devotional life. Quoting Thomas Oden, “‘I believe’…is to speak from the heart, to reveal who one is by confessing one’s essential belief, the faith that makes life worth living.”

Or, as the Ragamuffin sang, I believe what I believe is what makes me what I am…

They Call Me Trinity: Subordination vs. the Good Son

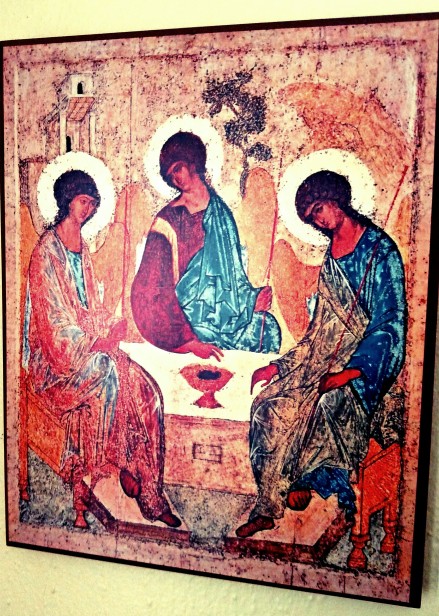

My copy of Rublev’s masterpiece, The Trinity

The maddening thing about being a Christian parent is driving home from church and asking your younger children, “So what did you learn today?”

After that startled I wasn’t paying attention look in the rearview mirror, they answer with quivering voices, “Ummm…to love Jesus and God?”

Which prompts an unsuccessful attempt to explain the Godhead. The sun analogy doesn’t quite work. Nor the water molecule. The challenge is complicated by the fact implicit in their answer: that the second person of the Trinity became man.

Don’t worry — other religious traditions don’t get it. Honestly, a lot of faithful Christians don’t, either.

If you are a Christian (and unless you’ve been asleep) you’ve probably heard about the ruckus that has erupted in evangelical/reformed circles in the past month over the nature of the Trinity. Specifically, a group of scholars, led chiefly by Bruce Ware and Wayne Grudem, posit that within the Godhead the Son is eternally, functionally subordinate to the Father. Equal in essence to the Father, but as Son having a subordinate role. This in turn is used to argue for the subordination of wives (women) to husbands (men). One text used to support this is 1 Corinthians 11:3, where Paul writes,

But I want you to know that Christ is the head of every man, and the man is the head of a woman, and God is the head of Christ.

The theological issue at hand involves the last clause: “God is the head of Christ.” Pulling out my ESV Study Bible I noticed that Frank Thielman’s footnote for 1 Cor 11:3 suggests something akin to functional subordination in the Trinity. But, as Andrew Moody points out, “there is a difference between Jesus’ eternal and human life…” This passage points to the relationship resulting from the second person of the Trinity having become man — the Jesus who, as our little ones tell us from the back seat, is to be loved with God.

The manhood of Christ is part of the reason the Antiochian-schooled archbishop Nestorius (431) struggled to accept the title theotokos (God-bearer, or in the Western Catholic tradition, “mother of God”) for Mary the mother of Jesus. In his mind this title overlooked the incarnation: God had become man, and it was his human nature to which the virgin had given birth. In his view Christotokos was a more appropriate title for Mary. But Nestorius’ critics, among them his Alexandrian political rival Cyril, accused him of splitting Christ into two persons, God and a man, instead of one person with two united natures. Nestorius denied this charge [I can’t pursue it here, but I suspect part of the controversy was linguistic, with Nestorius relying on Persian rather than Greek terminology to describe Christ’s person and natures].

I share this to further illustrate how complicated and delicate the job of describing the Godhead can be. An opportunity to pull over and ditch this conversation at the nearest restaurant open on Sunday can’t happen soon enough (with apology to Chick fil A).

In the case of the Son’s eternal subordination to the Father, passages like 1 Cor 11:3 don’t help. It isn’t the Trinity in view but Christ in the economy of redemption, i.e. the ministry of God’s Son after incarnation. Michael Bird (whose excellent blog is linked in the column to the right) expresses concern that subordination — even if qualified as “functional” — leads to a “Triarchy” instead of Tri-unity. And as Liam Goligher points out, the attempt to use examples of Christ’s subordination to God during his earthly ministry is anachronistic, reading the redemptive economy played out in time and space back into the ontology of the Godhead.

I’ve read a couple of things Goligher has written on this matter. While unrelenting in defending Nicene orthodoxy (and suggesting that those who don’t hold it shouldn’t teach) it’s clear that his aim is to bring those holding the subordination view back to a proper understanding of the Godhead.

The same can’t be said of a recent post at First Things by Carl Trueman, a church historian of first-rank and scholar I admire. Expressing his disappointment with the eternal subordination position (perhaps “horror” is a better word), he makes several statements that leave me cold:

It seems clear now that the evangelical wing of conservative Protestantism has been built on a theological mirage. Typically, evangelicalism focuses on Biblicism and salvation as two of its major foundations and regards these as cutting across denominational boundaries, pointing to a deeper unity. But now it is obvious that, whatever agreement there might be on these issues, a more fundamental breach exists over the very identity of God…

…Maybe it is time for those Protestants who disagree on this most fundamental and distinctive of Christian doctrines to face the implications and amicably to go their separate ways. Evangelicalism as currently constructed should be dismantled, as there is little of theological substance that holds it together…

…[W]hat does seem clear to me is that confessional Protestants need to think long and hard about their connections to evangelicalism, broadly conceived. There are other, better options out there…

In light of the last few weeks, the American conservative evangelical movement as a whole has been exposed as theologically thin in its doctrine and historically eccentric in its priorities…

Some pretty sweeping pronouncements. Why you want to be like that, Carl?

To be clear: I believe exactly what Trueman believes about the Trinity, which is exactly what the Nicene Creed sets forth. I realize it’s anecdotal, but everything I know about historical orthodoxy I learned first by reading evangelical scholars. To give one example, an article by Craig Blaising on the Council of Chalcedon for Bibliotheca Sacra, the Dallas Theological Seminary quarterly, ignited my interest in exploring the Church Fathers and the theology of the ancient church (which set me on a path that ultimately led to the Anglican communion).

Trueman is correct about the evangelical emphasis on the Bible and salvation for cutting across boundaries. In that process some novel and eccentric ideas crop up that require confronting and correcting. But calls for separation don’t simply clean up the theological work space; they result in the separation of whole groups of people from the conversation. People who need to hear what folks like Carl Trueman have to say.

Well, I would like to say something about the second person of the Trinity, prompted by an excellent podcast discussion at Mere Orthodoxy. While discussing the subordination controversy Derek Rishmawy used a word I really like: sonliness. For me, “sonliness” gets at something that can help us better understand the Son within the Trinity.

He is, after all, the Son — not the “Child.” The New Testament borrows from the Roman idea of sonship to illustrate rights and privilege of adoption into God’s family. Sonship involves being the adult heir to a father’s estate. He’s the heir because he is a responsible person, sharing his father’s interests with the intent to sustain if not expand the estate.

A child, by contrast, is subordinate to its father, being too young, too unaware, and needing to be told what to do. A son knows and shares his father’s purposes and desires; a child needs training and correction to understand what those desires and purposes are.

I remember hurrying home from work one day because a storm was coming, and I wanted to get the yard mowed before it hit. As I pulled up in front of the house I saw the grass had already been cut. My son came out on the porch and said, “I knew you would want that done before it started raining, dad.”

That is sonship. It says I can be at peace because he has taken over things exactly as I would want them. And may I add: you can be 40 or 50 or 60 years old and still be but a child to your own father, breaking his heart.

In the same podcast Andrew Wilson speaks of the “fittingness” of the Son to be the one sent into the world on the Father’s errand — not as a matter of functional subordination, but because it is what a son does. What is that errand? To seek true worshipers who will worship God in Spirit and in truth. This is what Jesus told the Samaritan woman by Jacob’s well.

Later, that “babbler” Paul faced the learned Stoics and Epicureans on the Aeropagus in Athens. His message?

“…[W]e should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone — an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent. For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead” (Acts 17:29-31)

Neither at Jacob’s well nor the Aeropagus do we find an explication of the Trinity. We get, rather, a call: a call to repent, a call to become true worshipers of the true God. God reveals himself as we are drawn by the Son through the Holy Spirit into fellowship. The medieval iconographer Andrei Rublev depicts this in The Trinity (ca. 1410). The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are seated at a table — and a place is open for you, viewer, on Sundays and other days, to join them. The Son gestures with two fingers toward the cup of salvation — the blood of the New Covenant he shed on the cross for the remission of our sins. This beautiful and theologically rich image shores up our understanding of the Trinity in whose name we are baptized. It unfolds something of the glory of the God we worship in the church.

But the church needs the prophetic edge of evangelism that goes into the byways and hedges, as well as the academies and offices, to seek and compel people to come in.

In doing those things that please the Father, in going out to win treasures for his household, the Good Son isn’t about tripping up those who can’t pass a pop quiz on the nature of the Trinity. Whether it was through crying out to him, “Son of David!” or just nagging persistence, Jesus honored faith wherever he found it.

There’s plenty of time (i.e., eternity) to learn and grow in our understanding and appreciation of the Trinity. The time to repent is now.

Dogs of Peace Still Guide You Home

The cool thing growing up the son of a disc jockey was connecting with him through the radio as he spun the great tunes from the seminal period 1967-76. By the time I came of age my musical sensibilities were set in stone — hence, the ’80s were a downer for me while the ’90s marked something of a return to form.

The cool thing growing up the son of a disc jockey was connecting with him through the radio as he spun the great tunes from the seminal period 1967-76. By the time I came of age my musical sensibilities were set in stone — hence, the ’80s were a downer for me while the ’90s marked something of a return to form.

In the summer of ’96 I bought a copy of Speak by Dogs of Peace, what was thought to be a one-off from a foursome of Nashville session players: Gordon Kennedy (guitar, vocals), Jimmie Lee Sloas (bass, vocals), Blair Masters (keyboards, bgv’s), and John Hammond on drums. I won’t take the space here list the luminaries these guys have played with or for, or produced. They’re musicians’ musicians, so unsurprisingly Speak was easily among the highlights of the decade.

My best buddy and former workmate is himself a guitarist with gigging and recording experience. I would bring my cassette copy of Speak and we would blast it in the car while working. We analyzed it. We argued its technical details. We caught its reference points: Wings, Pink Floyd, James Gang, Hendrix, among others. He was able to break down Kennedy’s guitar leads and explain how he achieved certain tones, as on “Do You Know,” whose twin solos match the aching grandeur of Gilmour on “Comfortably Numb.”

Unwinding from the day I’d go down to the basement and play it again, having sent my daughters (13 and 11 at the time) to bed. I didn’t know it at the time, but they were listening, too. Especially to “Thrown Away” — they loved that track. It spoke to them at those transitional ages. Proud of those gals for their good musical tastes. Chips off the old block.

Can’t sleep without the light on…

But things change over twenty years. I confess I’m lost when it comes to today’s hipster music. No offense, but I don’t get what’s so enthralling about ukuleles, glockenspiels, dead-pan lead vocals and wordless choruses that go,

oohhhh-wayyy-oohhh, oh-oh way-ay, oh-oh-whoah….

[probably the generation that grew up watching Arthur and caught that episode about the Finnish hologram band, BINKY]

Anyway, it’s a relief that Dogs of Peace weren’t an one-off after all. After twenty years of doing myriad other things the group reformed and released Heel in April of this year. The cover art and title allude to the proto-evangel in Genesis 3:15: God curses the serpent for his deceit and promises that the “seed of the woman,” i.e. the virgin-born son, would crush the serpent’s head (check out the bonus track, “Crush”) — though the serpent would manage to inflict a deadly wound to his heel.

The title also plays on the “dog” metaphor.

Heel is arranged in three sets of three songs, with a closing medley/postlude. The opening tracks come out of the blocks big and bold: detonating drums, swirling strings, muscular riffs. They combine a snarling guitar tone a la Jimmy Page with an expanding, boiling thunderhead of a sound reminiscent of Kerry Livgren’s arrangements. While the most bombastic of the album, these songs establish a more chiseled, classic rock sound than the alt edge of the first record. They also introduce recurring themes: intercession (“One Flight Away”), interposition (“Sacrifice”), and light/darkness:

Looking at the painting of Van Gogh’s Starry Night / with a brush he paints a riddle / a church in the middle, but somebody’s turned out the light… (“Dark Without”)

The second trio of songs finds the band broadening the scope, shifting between moods while infusing the music with their characteristic humor. “All This For a Piece of Fruit” winsomely plays on the fall of human nature — with more than a enough cowbell to fill Bruce Dickinson’s prescription. And a few of those previously unnamed luminaries begin to show up: Ricky Skaggs showcases his mandolin on “Only the Gold,” but this isn’t a salute to Dr. Ralph Stanley (deserving as he is). Rather, Steely Dan-tight harmonies punch through an Alan Parsons “I Robot” soundscape at breakneck pace. Skagg’s mandolin solo is sublime beyond words.

Speaking of Steely Dan, piano ace Michael Omartian makes his cameo as the album transitions into the third section, opening with one of the its best tracks, “Friend of the Groom.” A jocose nod to John 3:29, this is straight-up Southern rock more stout than a pot of black coffee. Fat guitar, funky bass, and Omartian’s boogie piano create conditions for a heavy foot on the gas pedal. You can tell the band is into it: at the intro to the second verse one voice says “Yep” while another answers “Right.”

Shifting gears, the elegant “Healed” is graced with a poignant guitar solo from guest Peter Frampton. It’s a meditation on what mortality has been transformed into for believers: we might not leave this present cosmos cured, but we can assuredly leave it healed. More on that in a moment.

Meanwhile, another confession: I’m not into praise and worship music. Visiting churches that use this style I’m the guy hands-in-pockets staring at the screen while everyone else is enraptured, eyes closed, singing the lines from memory. But if the songs were more like “He’s the Light of the Word” I might get into it. No congregation could sing at this level, but I could envision a tastefully scaled-down version making the rounds in churches. Whiteheart’s Rick Florian, PFR’s Joel Hanson, and the McCrary Sisters join in to create a gospel choir for a rousing outro. Following a change of key one of the McCrary’s begins to sing and Sloas hits a booming note on his bass that makes the hair on the back of my neck tingle.

The final verse declares:

Jesus, he is matchless / see the wounds of God’s wrath / Brilliant in the chaos / illuminating my path…

A deeply held evangelical conviction is that Christ’s death deflects God’s wrath for sin away from those who believe in him, i.e. substitutionary atonement. This idea, based on passages like Isaiah 53:4-8 and the reflections of St. Anselm and John Calvin, has in more recent times fallen out of favor, giving way to Christus Victor and other plausible theories of the efficacy of his death. But we’re talking about Christ’s death, a matter of cosmic weight. I agree with most of these models — including the sinner’s substitute idea.

I was recently queried about this by some hipsters.

“Why, yes,” I responded. “I do happen to believe in it.”

Their smiles faded. I could see the look in their eyes: Old guy holding to a 15th century heresy. Everybody keep cool, keep smiling, and wave your hands…

oohhhh-wayyy-oohhh, oh-oh way-ay, oh-oh-whoah….

Yeah, whatever. Like I said, some things change over twenty years.

In the time that’s passed since 1996 I’ve added three more children to my quiver. A job change in 2012 separated me from my guitar-playing sidekick and the daily camaraderie we enjoyed. My dad developed Alzheimer’s. Two winters ago his condition took a decisive turn for the worse. Around that time one of my daughters — the one who was 11 when Speak came out — gave birth to a second grandchild, a baby girl, via c-section. A couple of days later my gal started hemorrhaging. The bleeding was out of control; she faded in and out as doctor’s struggled to stabilize her condition.

It’s a drama played out thousands of times a day in hospitals, nursing homes, accident scenes, battlefields and other scenes across the globe. We who stand by and watch and pray ask ourselves: Did I say and do all the right things?

Helplessness isn’t the right word. Irrelevance is probably closer. Because whether loved ones pass through the dark valley or come back out of it, only the Shepherd can go with them, lighting the way.

Against all instinct and understanding, this is the point where the dog must heel. And stay. And wait as the Master does his inscrutable work.

Shine. Let it shine. Keep it on…….

Turns out my daughter was raised up from her sickbed. Dad we later laid to rest — until the resurrection. One cured, the other healed. But the same Shepherd over both…

So how do the Dogs bring this gem of an album home? The finale is a dramatic, Abbey Road-like medley expanding the “light of the world” motif.

“Light into the Darkness,” which Kennedy and Masters built around a Sloas bass line, reminds us that having engaged his seemingly chaotic creation the Artist will not abandon it. This, incidentally, is at the very heart of God’s righteousness. “He can work with this,” we are assured.

Our response, our vocation is to shine (“Shine Dog”), not hiding this light under our bowls. But lest we get carried away in our endeavors, we’re drawn back to a be still moment: “3:16,” from John’s gospel, the most recognized and quoted verse in the Bible, brought to remembrance.

Heel closes with a slide guitar instrumental of “Amazing Grace.”

Hmm. Nothing I can add to that besides, “listen to the record.” Maybe they’ll do another — maybe Fetch, or something like that (though, at this rate of output I’m not sure I’ll be around for it). Either way, Dogs of Peace have left us with a pair of brilliantly conceived and finely crafted artifacts that point restive hearts toward home.

Christian Zionism Left Behind

Back in 1998, I think it was, I told a buddy of mine, “You wait. Once Y2K passes without incident you’ll see dispensationalism go into steep decline.”

I’m a dang prophet.

Dispensational theology has indeed lost ground since the turn of the century, but this owes to factors beyond the lack of fulfilled apocalyptic expectation. There’s been a shift of allegiances in the American evangelical world. “Reformed” is the thing these days. “Left Behind” theology, as dispensationalism is often called, is now laughed off as the provenance of literalistic, sensationalistic rubes. Others seeking connection with the ancient and historic church have moved toward liturgical expressions (Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican) where amillennial eschatology rules and rapture-talk is eschewed.

But dispensationalism entered a new phase of complimentary hermeneutics and dialogue with Reformed camps starting in the late ’80s, and has undergone noteworthy development and change.

First, we should note that dispensational concepts weren’t “invented” in the early 19th century. Many of the early church fathers like Methodius, for example, drew up rudimentary “charts” to trace obvious changes in God’s dealings with humankind over the ages. As the joke goes, any Christian who worships on Sunday instead of Saturday (the Jewish Sabbath) is dispensational, recognizing that something fundamentally changed after Christ’s resurrection.

In the early 19th century J.N. Darby, a Trinity College classical gold medal scholar turned Anglican deacon, got fed up with the rampant corruption in the Church of Ireland and decided to meet with a small group who felt similarly disenfranchised by the denominations in Dublin. While recuperating from a riding accident Darby began ruminating on the nature, calling, and destiny of the church. As his ecclesiology developed he detected a break between the New Testament church and Old Testament Israel (a century and a half later progressive dispensationalists would recognize that this break wasn’t so clean). This distinction became the basis of the first truly systematic, dispensational theology.

“Can I be post-trib now?”

Applying — perhaps subconsciously — a neo-Platonist dualism to his scriptural observations, Darby believed the church to be God’s “heavenly” people, with Israel as the “earthly” people of both the past and the future.

It’s important to understand that ecclesiology, not eschatology, was the basis for Darby’s system. The latter was an implication of the former. That he saw a future, earthly millennium ruled by Christ was nothing new or novel. Many of the ante-Nicene fathers, most notably St. Irenaeus, saw the same thing. But Darby placed a renewed Israel at the center of that kingdom; a nation that would at last inherit all the unique and specific promises prophesied in the Old Testament. The church, meanwhile, would oversee this phase of salvation history from on high, until the final consummation of all things.

Most people have either not heard of Darby or seen only disparaging (and often inaccurate) statements about him in “Left Behind”-bashing articles. The dispensationalism most widely known today was influenced by the Scofield Reference Bible. The system found in C.I. Scofield’s footnotes is similar to Darby’s, but differs in certain respects. Being more of an interdenominational missions guy, Scofield was less concerned with the details of ecclesiology than with prophecy. Through him and his protege Lewis Sperry Chafer (co-founder of Dallas Theological Seminary with Anglican theologian W.H. Griffith Thomas), the idea of a pretribulational rapture of the church (1 Thessalonians 4:13-18) spread through American evangelical circles.

In the pre-trib rapture scheme the “heavenly” people are caught up to meet their Bridegroom in the air, leaving the rest of the world to endure a period of unique tribulation, a.k.a. the “time of Jacob’s trouble” (Jeremiah 30:7). This particular tribulation will have the effect of shaking Israel from unbelief, causing her to repent and believe in Jesus, preparing her to meet him as king.

But notice: consonant with Paul’s anguish over his kinsmen in Romans 9, Israel in its present state is seen as lost, in need of repentance and faith toward Christ (Acts 3:20-21). Israel was a kingdom before God in the past age and will be so again in the age to come. But for now? More than a few Jews around the globe reject the modern Zionist project because, according to their understanding, “Israel” cannot exist in blessing and peace until Messiah comes. As the Zionist movement was gaining traction in the early 20th century one prominent dispensationalist, Arno C. Gaebelein, cautioned,

Zionism is not the divinely promised restoration of Israel… Zionism is not the fulfillment of the large number of predictions found in the Old Testament Scriptures, which relates to Israel’s return to the land… It is rather a political and philanthropic undertaking… The great movement is one of unbelief and confidence in themselves instead of God’s eternal purposes.

Which brings us to Christian Zionism — and my thesis: that dispensationalism and Christian Zionism, though easily conflated, are not the same thing.

Granted, it’s an easy step for a dispensationalist to become a Christian Zionist, and many (perhaps most) are. But there are many people that can be categorized as Christian Zionists who aren’t dispensational in the least.

What exactly is Christian Zionism? It’s an attitude of support among Christians for the modern state of Israel. Its best-known exemplar is pastor and televangelist John Hagee. It’s based not so much on a distinction between the church and Israel as the promise and warning of Genesis 12:1-3. Speaking to Abraham, God said,

“Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you.

“I will make you into a great nation,

and I will bless you;

I will make your name great,

and you will be a blessing.

I will bless those who bless you,

and whoever curses you I will curse;

and all peoples on earth

will be blessed through you.”

“Nation” here is held as a political entity, Israel as kingdom in the Old Testament and the modern state of our time. Regardless of denominational or theological persuasion, a Christian Zionist is one who, a) believes God has given Israel the land of Palestine, b) believes that Israel enjoys unique blessings — regardless of Jewish unbelief in Jesus as Messiah, c) believes that individuals and nations who support the modern state of Israel will be blessed for doing so, and d) believes that those who don’t support Israel will be cursed.

A bit snarkier, we could add, e) believes that Israel is America’s strategic ally and “best friend” in the Middle East, f) despises the Muslim world, and g) doesn’t get that Middle Eastern Christians have quite a different opinion of the Israeli government from American Christians (anyone recall what happened when Ted Cruz told a group of Middle Eastern Christians that they should support him in supporting Israel?).

Christian Zionist convictions are held with an extraordinary ardor. Israel is supported in all she does because all that she does is God’s will, without qualification. Its slogan on social media is, “Stand with Israel!” (while more than a few Israelis are unhappy with their government’s policies). I was recently unfriended by a Catholic acquaintance on Facebook for making a critical comment about certain aspects of Israeli government policy. Yet, that same gentleman loathes dispensationalism as a damnable heresy.

Dispensationalism is not the same thing as Christian Zionism. That it looks for a future restoration of Israel (a topic to explore further at another time) does not necessarily infer that the present political state of Israel fulfills specific Old Testament promises or unconditional blessings. If anything, dispensationalism admits that modern Israel could be in for some tough sledding during “Jacob’s trouble” (cf. Mark 13:14-26).

I close with these thoughts from Craig Blaising, provost at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, patristics scholar, and dispensational theologian:

In their enthusiasm for the political resurrection of Israel, some [Christians] seem to have lost sight of the particular activity of [Jesus] the Son of David in this dispensation — which is bringing about reconciliation and peace between peoples. Some have publicly advocated carte blanche support for any policy enacted by the state of Israel. But if political policies uphold injustice, how can Christians support it? How can Jewish or Gentile Christians today support Israeli injustices when Jewish prophets in the Old Testament condemned the authorities in Jerusalem for similar injustices, often to the prophets’ own peril? There were no greater supporters of the Jewish people and the future of Israel under God than Moses, Samuel, Amos, Elijah, Habbakuk, Isaiah, and Jeremiah. And yet not one of them confused their commitment and desire for the blessing of Israel with support for or toleration of injustice (Progressive Dispensationalism, 1993, pp. 296-97).

N.T. Wright vs. the Piano Man

Without a doubt, N.T. Wright is a rock star.

There’s no other way to describe an Anglican bishop who commands an interview from Stephen Colbert on The Colbert Report. Wright has written dozens of books, many of which resonate with Catholics on one hand and bearded, bespectacled bobos (and their ladies) on the other — especially where Wright appeals to sundry social justice issues. In the fall of 2013 he published his latest tome, the 1,600 page Paul and The Faithfulness of God, a work that sets forth a unified metanarrative of God’s covenant righteousness and the apostle’s place in bringing that narrative to Gentiles.

Interesting, then, that at roughly the same time Wright’s magnum opus appears another, much slimmer volume arises to take him on  like a diminutive fighter jet scrambled to buzz Godzilla. I’m referring to Justification Reconsidered by Stephen Westerholm, professor of biblical studies at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Westerholm, incidentally, earned an Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Music (Toronto) in piano performance. He apparently has some wicked keyboard chops to go along with his formidable scholarship in scripture.

like a diminutive fighter jet scrambled to buzz Godzilla. I’m referring to Justification Reconsidered by Stephen Westerholm, professor of biblical studies at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Westerholm, incidentally, earned an Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Music (Toronto) in piano performance. He apparently has some wicked keyboard chops to go along with his formidable scholarship in scripture.

Justification Reconsidered clocks in at a compendious 99 pages. Westerholm lines up the heavy hitters of the New Perspective(s) on Paul, aiming to throw nothing but K’s — retiring Krister Stendahl, E.P. Sanders, Heikki Räisänen, Wright (batting clean-up), James D.G. Dunn, and Douglas Campbell in order. While his defense of a traditional, Augustinian-Lutheran view of justification is developed over the course of the book, our focus here is on his engagement with the household name, Wright, that spans 23 pages.

Westerholm’s tone is irenic. He lauds N.T. Wright for his great insights and recognizes common ground where it exists. He acknowledges, too, that Wright takes Paul seriously (rather than finding him incoherent, as some modern Pauline scholars are prone to do), and traces the cohesive thrust of Wright’s narrative:

In Wright’s version of the story, the covenant God made with Abraham assigned the people [Israel] itself, as a nation, with the task of undoing Adam’s sin. Israel was to play ‘the crucial, linchpin role’ in God’s plan to save the world…

But, of course, so understood, the divine plan was doomed from the start. Wright duly notes that Israel shared in the effects of Adam’s sin and was thus in no position to undo it by obeying God’s commands…

Wright is as insistent as any that the cross and resurrection of Christ represent the climax of God’s redemptive plan, but something of his distinctive account of Israel’s story is carried over into Christ’s redemptive work. Whereas Christ is traditionally believed to be the representative human being in his sacrificial death (cf. 2 Cor 5:14-15), in Wright’s retelling he is, in the first place, the representative Israelite: as Israel’s representative, not only does he fulfill the task that the nation was unable to perform…but he also takes upon himself the curse of their failure to perform it.

So the key to Wright’s narrative is the idea of covenant — from Abraham through Israel to the true Israelite, Jesus — and the inclusion of all into that covenant who believe in Jesus. God’s covenant faithfulness (= righteousness) is borne out by his gracious reception of Gentiles who believe in Christ.

Which brings us to the issue at hand: justification. With N.T. Wright we might say that justification involves 1) law court, and 2) lunch counter (okay, I’m being cute with the latter). Legally speaking, those who believe in Jesus are declared righteous. This does not mean they are actually righteous, but reckoned so on account of their inclusion within the covenant people. Moreover, since they now participate in the covenant they cannot be excluded from the “lunch counter,” i.e. table fellowship. This is Wright’s understanding of justification in Galatians 2:11-16a (excluding, as Westerholm notes, 16b). It underpins views on social justice that enamor him to Millennials and others of like mind: at God’s lunch counter there is no discrimination. In his own words,

We are forced to conclude, at least in a preliminary way, that ‘to be justified’ here does not mean ‘to be granted forgiveness of your sins’…but rather, and very specifically, ‘to be reckoned by God to be a true member of his family, and hence with the right to share table fellowship.’

Now, N.T. Wright isn’t saying that people do not have to be forgiven their sins, or don’t receive the same; scripture plainly declares this to be so (e.g. Eph 1:7). But for Wright, “justification” is a legal verdict that declares who can sit at God’s table.

So, what’s the big deal?

Few would argue with the implications of table fellowship. It is quite true that in the new dispensation God receives all, circumcised and uncircumcised, those who eat kosher and those that don’t, those that celebrate certain days and those that don’t. The basis of reception is faith in Christ. But are covenant inclusion and reception equivalent to justification?

Stephen Westerholm traces the word righteous (“just”) throughout the Hebrew scriptures and finds a different emphasis. People are righteous, not by declaration, but by what they do.

The ‘righteous’ are thus those who do what they ought to do (i.e. righteousness). One is reminded of the words of 1 John: ‘Don’t let anyone fool you: It is the one who does righteousness who is righteous’ (1 John 3:7; cf. Rev 22:11). The truth of this seemingly self-evident observation is confirmed by Ezekiel 3:20 as well: ‘When a righteous person turns away from their righteousness and commits iniquity…that person shall die for their sin; the righteous deeds that they have done [on the basis of which, they were once ‘righteous’] shall not be remembered.’ Interestingly enough, even things — scales (when accurate), a (figurative) ‘path’ or commands (when morally appropriate) — can be said to be ‘righteous’: when, that is, they are what they ought (or purport) to be.

He goes on to quote Leviticus 19:35-36 (and others passages) to illustrate the point about righteous “things” — and here I fight the urge to go on a tangent about free vs. rigged markets, monetary inflation and related topics that, as a student of economics, I find important in regard to social justice. But the point is well-taken: you can’t simply say a set of scales is “just” when it is in fact unbalanced (and no set of scales can “sign up” for the covenant). We cannot say a wicked person is justified when her conduct is manifestly wicked; in fact, Deuteronomy 25:1 requires judges to judge on the basis of the person’s character — the covenant notwithstanding.

The Ezekiel passage cited above ought to give us pause. It’s pretty self-evident that we have good days and bad, times when we do the right thing and times we don’t. If unrighteous deeds negate righteous ones, we have a problem — one that Paul sums up when he writes, “As it is written: There is no one righteous, not even one” (Rom 3:10, cf. Psalm 14:1; 143:2). But if scripture admonishes a judge to judge on the basis of a person’s deeds, how can God himself be just and allow imperfect people into his kingdom?

“Paul delights in the paradoxes of the gospel,” writes Westerholm, who takes Paul as seriously as Wright. God can regard an unrighteous person as just — not on the basis of covenant inclusion (and certainly not because of what she has done, or failed to do) — but because of a divine transaction on the cross:

The compact language of 2 Corinthians 5:21 seems to mean that, on the cross, God worked a dramatic exchange: the sinfulness of human beings was made Christ’s, so that his righteousness might be made theirs.

Righteousness, the state of being “justified,” is a gift given by God in exchange for our sinfulness, which was borne on the cross by Jesus. We are righteous (justified), not because we belong to the right people, but because we’ve been made right with God through the death of his Son.

“I get that,” you may reply; “but how is this distinguishable from Wright, who says that those who believe in Jesus get the benefits of justification?” It’s important to underscore, again and again, the personal and existential nature of faith meeting the faith. In dialogue with Krister Stendahl (chapter 1), Westerholm points out that Greco-Roman pagans were neither 1) acutely exercised about specific sins, nor 2) beating the doors down to enter God’s covenant through the Jews (i.e. Abraham). But Paul’s preaching to both Jew and Gentile followed the imperative nature of passages like 1 Thessalonians 1:9-10 and Ephesians 5:3-6. God’s wrath is coming upon the whole world for its unrighteousness; the only escape is through Christ. The Jews had a long-standing apocalyptic tradition; the Greeks, anxiety over how the gods might reckon with their lapses in virtue. A gospel that proclaims the end of the old, unrighteous order, the inauguration of a new, righteous one, and safe transfer for the believer from the former to the latter found resonance in many (though not all, or even most) of Paul’s hearers.

The goal, according to Paul, is to be “found” on the day of God’s visitation, “not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law [which amounts to no righteousness, but that’s a topic for another day], but that which is through faith in Christ — the righteousness that comes from God on the basis of faith” (Phil 3:9).

“What is your name?” was not only the first question Monty Python’s King Arthur had to answer before crossing the bridge of death; it’s the first question in the Anglican catechism. The gospel calls for a response from each of us individually. The faith community, which expresses itself at God’s lunch counter, is composed of such creatures. While covenant faithfulness is certainly an important aspect of God’s righteousness — and we can thank Wright for highlighting it — Westerholm shows us that God’s faithfulness is more cosmic in scope: faithfulness to creation, which means expelling unrighteousness while saving those who obey the gospel. The center-right scholar Westerholm succeeds in reiterating justification in terms that are recognizable in a traditional, Augustinian-reformed-evangelical framework.

N.T. Wright may be the rock star. But on this score Stephen Westerholm plays a better tune.